By Laura Warne

Communications Coordinator

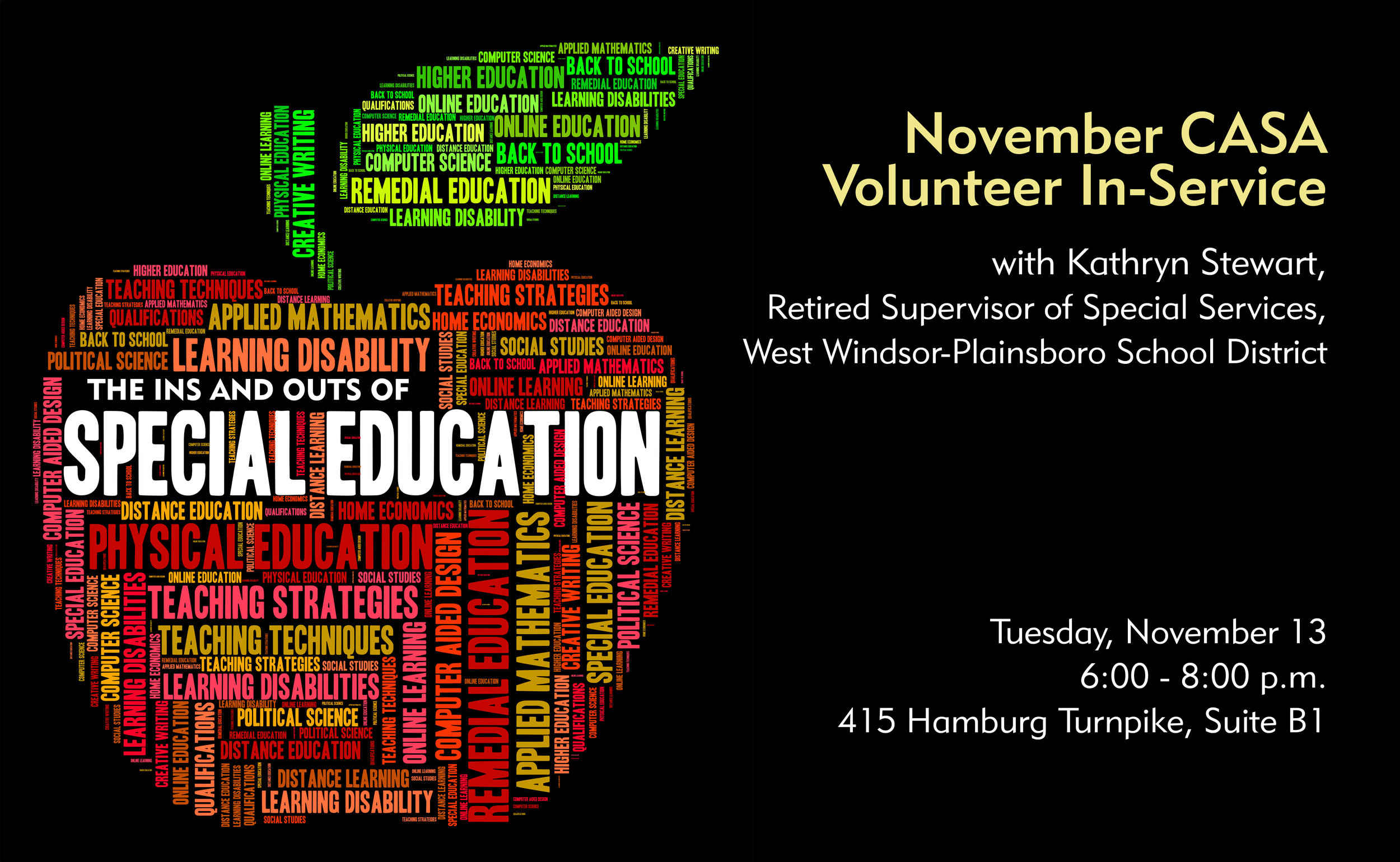

Passaic County CASA hosted an In-Service Workshop for CASA Volunteers entitled “The Ins and Outs of Special Ed.” Kathryn L. Stewart, Retired Supervisor of Special Services at the West Windsor-Plainsboro School District, led the workshop, drawing from her 39 years in education, including roles as a teacher, a learning consultant, and a Supervisor of Special Services. She offered useful information for CASA volunteers who are concerned about their assigned child(ren)’s academic performance and what to do about it.

One point she emphasized was that the earlier a learning difficulty is addressed, the better the outcome. When you see a child is having trouble in school, whether it is difficulty with math, reading, understanding instructions, completing homework, or even behavioral issues, CASAs shouldn’t be afraid to voice their concerns. One person to start communicating concerns with could be the child’s resource parents, asking them about whether they see this as typical performance or a new issue. Another place to go could be the child’s teacher, requesting their perspective on how the child is doing relative to other students in the class.

If it is a child’s behavior that is of concern, Ms. Stewart urged patience and compassion. School can be challenging for students with stable home environments, never mind those who have experienced turmoil at home or been uprooted multiple times. If a child is struggling, they may prefer to act out and disrupt class, rather than risk being labeled “stupid.” Self-esteem can be a real struggle for children when they encounter learning difficulties. CASAs can be of particular service by helping those children focus on what they do well, including admirable skills and personality traits.

Before special education is discussed for any child, Ms. Stewart urged CASAs to consider what could be done to address the issue(s) in the child’s regular classroom. If a child is struggling with reading, could a tutor help? Would having the child sit in the front row make a difference? Consider ruling out medical concerns, such as eyesight or hearing. Is English the child’s native language? If not, could that be the source of the difficulty?

Ultimately, if the individuals involved suspect that the child’s learning challenges will require further intervention, the next step to pursue is an evaluation by the school’s Child Study Team. This is an in-house group consisting of a learning consultant, school social worker, and school psychologist, whose job it is to pinpoint the source of the challenges a student is facing. However, because CASAs are not guardians of the child, they cannot directly make an evaluation request on their own; instead it must go through the child’s resource parent, biological parent, a teacher, or the court. In general, it is always best to work cooperatively with the parties involved to build consensus on an issue, and while school districts do have the right to refuse an evaluation, most will respond agreeably.

Another detail Ms. Stewart suggested was, when possible, CASAs should encourage the school to keep the child’s biological parents informed about developments and ideally signing off on the child’s evaluations. This can help make decisions easier down the road. CASAs should also not be afraid to ask questions if they don’t understand a term or acronym being used by the Child Study Team. They should also remain focused on the specific action items that the school will take to address the child’s difficulties. As with so many things, sometimes if the school knows that someone is watching it will be sufficient to ensure that the process progresses and nothing falls through the cracks.

If the child is eligible for Special Ed and related services, the school’s Child Study Team will produce an Individualized Education Plan, or IEP, which is a legal document outlining how the child’s learning difficulties will be addressed. A new IEP must be drafted every year, and new testing must be considered every three years.

When children move schools, IEPs don’t always move with the child, or they may arrive after the child has spent several weeks in school feeling lost and frustrated. CASAs can be of assistance by helping to ensure that a child’s IEP be sent to the new school as quickly as possible.

For CASAs with children 14 and older, that IEP must address how that child will transition to life after graduation. This is an opportunity for CASAs to help evaluate realistic options, including vocational programs, apprenticeships, and job training.

Ultimately, CASAs are in a great position to help children thrive educationally, and shouldn’t be afraid to use their voice to speak up in their child’s school. Special Educators are there to help, and few things impact a child’s future more than receiving a quality education.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Passaic County Court Appointed Special Advocates (CASA) empowers volunteer advocates to champion the best interests of children in the foster care system. Our monthly In-Service Series features expert speakers on topics of relevance to CASA volunteers with the goal of promoting continual learning and advancing effective advocacy of children in the foster care system.